By Marion Miclet | @Marion_en_VO

From Malcolm in the Middle to House of Cards, Fleabag and The Serpent Queen, the highly efficient TV trope of breaking the fourth wall is having a moment. And what, if anything, has changed since its introduction on our television screens?

Shall we redecorate?

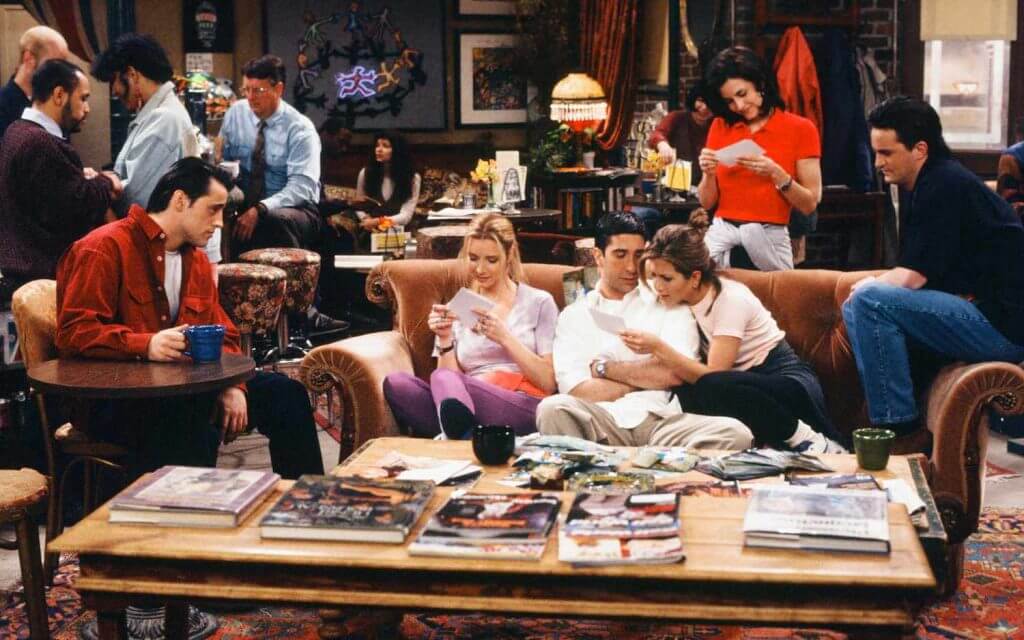

So what is the fourth wall, exactly? The term is attributed to French philosopher Denis Diderot (Discours sur la poésie dramatique, 1758), in relation to the theater: the stage is framed by three walls, plus an invisible one. This peculiar fourth wall allows the audience to see what is happening in the realm of the performance, while also safeguarding the make-believe elements of the play. Following this convention, the actors behave as if the spectators – and therefore, in film and television, the camera – do not exist. In a classic comedy like Friends, the usual formation of the six friends is an outward-facing half-circle. Remember the orange couch?

And yet, they never look in our direction. The fictional pact is intact.

Consequently, the destruction of the fourth wall is a bold choice: it interrupts the suspension of disbelief necessary to immerse ourselves in the story. Just imagine what it would feel like if Chandler or Rachel suddenly looked us in the eye! Yet, many emblematic TV shows daringly use this disruptive narrative and stylistic strategy. The sitcom Malcolm in the Middle is innovative in this regard. Fully aware that he is being watched, the main character continuously shares intimate details about his life. Even though the primary goal is to make us laugh, when he stares at us, Malcolm puts us in the position of the voyeur, and alters the usually passive experience of watching television. So how and when do TV series mobilize this trope? Which shows have successfully made it their signature? Let’s consider the history of breaking the fourth wall and the impact it has on the boundaries between fans and fiction.

An ubiquitous trend

The first TV series to break the fourth wall – The Jack Benny Program (1932-1955), The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show (1950-1958) and, later, Moonlighting (1985-1989) – put the emphasis on humor and empathy. Once the initial surprise has passed, they invite the viewers to feel included, by making them both confidants and witnesses to the trials and tribulations of the heroes. In the same vein, many mainstream teen dramas used this technique in the 1990s as a rite of passage to connect with their audiences at a time of emotional upheaval. What could be better, indeed, than to be gazed at by a cool, conspiratorial character (as seen in Parker Lewis Can’t Lose, Saved by the Bell, Clarissa Explains It All and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air) to feel special?

Teen series (…) have used the trope as a tool among others to bring the storytelling into surrealist territory.

Even pioneering teen shows such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Skins dabbled in breaking the fourth wall. Alas, this forced familiarity between the main protagonists and the viewers tends to veer into a caricature of the cult comedy Ferris Bueller’s Day Off released in 1986 which, to this day, is still one of the most acclaimed examples of fourth wall breaks in film history. Less heavy-handed in their approach, the recent hit Euphoria and the offbeat Croatian drama Nemoj nikome reći have used the trope as a tool among others to bring the storytelling into surrealist territory.

Metafiction

As we can see, breaking the fourth wall challenges – momentarily or constantly – the symbolic separation between fans and fiction. Furthermore, it can mean that the characters are aware that they are part of the story and sometimes call attention to it. For instance, in the new Marvel production She-Hulk, Tatiana Maslany plays the part of a lawyer-superhero who not only talks to the camera, but often grabs the reins of the narrative. To the point where she burst into the writers’ room to give her opinion on the finale. She doesn’t break the fourth wall, she annihilates it! That being said, the undisputed champion of inside jokes and meta references is Abed from Community (Danny Pudi). Hilariously sprinkled throughout, his knowledge of sitcom plot conventions is one of the show’s strongest suits.

One might think that the next frontier in the art of breaking the fourth wall is the mockumentary genre that has been popular on television since the early 2000s (Parks and Recreation, Modern Family, What We Do in the Shadows). But, here, the destruction is artificial. When Michael Scott confides to the camera, we know that he does so inside the fictional world of The Office. The fake documentary style is a comical device.

In an aside

The concept of breaking the fourth wall continues to evolve through TV series featuring an omniscient narrator (Augustus Hill in Oz is a classic example). These all-knowing voices who share their most intimate thoughts with the audience transform television viewing into an immersive experience. Whereas in Mr. Robot we are dealing with the figure of the unreliable narrator and end up descending into madness with him, in House of Cards the candidate played by Ian Richardson/Kevin Spacey exposes the undoubtedly evil workings of politics. When he addresses us directly, there is no more doublespeak. We become complicit in his crimes… and enjoy it all the more because our integrity is protected by the fictional frame.

The only rebellion [those characters] have access to is railing against the rules of the narrative, so speaking to the audience becomes their way-out.

Series inspired by true events that break the fourth wall are even more disturbing: they invite us into the minds of antiheroes whose impact on society – past or present – is palpable. From Catherine de’ Medici (Samantha Morton) in The Serpent Queen, to Anne Lister (Suranne Jones) in Gentleman Jack and the burnt-out OB-GYN portrayed by Ben Whishaw in This is Going to Hurt, these characters all feel trapped in an oppressive system. The only rebellion they have access to is railing against the rules of the narrative, so speaking to the audience becomes their way-out. In this sense, these shows make us question how we see the world and force us to pick a side. It doesn’t make for the most comfortable experience, which is exactly why these stories are so thrilling. And the fourth wall breaks feel more justified than ever.

Fleabag, a textbook oversharer

And what about Fleabag? Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s groundbreaking show is a masterpiece in the art of destroying the fourth wall with no less than 232 occurrences. It compiles every single variation of the technique listed so far: the disconcertingly direct address, the conspiratorial humor, the feeling of inclusion. And just like the other characters mentioned above, the heroine opens up to us about her deepest, darkest secrets. But instead of experiencing relief, she falls into a codependent relationship with her rapt fans who give her an excuse to distance herself from her issues while also validating her behavior.

In the second season, when she is finally able to develop a meaningful connection with Andrew Scott’s “hot priest” character, he notices that she is entangled in a special relationship with… who exactly? His curiosity is only matched by our astoundment when he starts to look towards the camera. And that’s how the boldest rom-com of these past few years (which inspired the structure of the Belgian TV production F*** you very, very much and the French remake Mouche) not only shatters the fourth wall, but also the fifth! Who will succeed Fleabag as the next television bulldozer?