By Laurence Herszberg, General Director of Series Mania and Pierre Ziemniak, Project Manager for Series Mania

Tribune published in Le Monde, November 21, 2020.

It is to TV what the little black dress is to the female wardrobe – practical and all-purpose, the police drama is an iconic part of television. It sprang into being at the same time as the medium itself and is much appreciated for its dramatic effectiveness on every continent. One episode of a so-called “procedural” police drama guarantees mystery, an investigation, and an outcome brought on by a team of law enforcement officers in under an hour. Easier to digest than its literary counterparts, this cocktail of false leads, sweat, and blood has been regularly keeping TV audiences on the edge of their seats for decades, without having to give its formula any major makeovers, and – and this is the real clincher for private networks – it lends itself easily to commercial breaks. It is easy to understand, given these wonderful features, that the genre has become a cornerstone of television – to the point of embodying, in the collective imagination, a certain idea of the institution it portrays, from field workers to high-ranking officers.

police dramas are now on trial. What happened, how did the mirror break?

Yet it is this link between law enforcement officials and their dramatic representation that is now under critical fire in the US, where systemic racism and the brutal repression of the ensuing protests blew up in the world’s face over the course of this election year. This toxic climate has only been exacerbated by the White House’s current occupant, who has consistently issued calls filled with authoritarian rhetoric on Twitter, accidentally quoting the name of an iconic show in the process with his insistence on “LAW AND ORDER!” What we’re seeing here is a serious crisis of representation in real time: while they were meant to be entertaining reflections of a job that is almost begging to be fictionalized, police dramas are now on trial. What happened, how did the mirror break?

The grievances are many. These were listed by American civil rights defense organization Color of Change in January, then taken up by a whole slew of critics; they include, in no particular order: the fact that breaches in the code of conduct by police characters are regularly minimized by their superiors; the quasi-systematic justification of the use of force on these shows; the lack of black victims in the investigations that are shown on-screen; not to mention the one-sidedness of the point of view, which focuses on law enforcement representatives, around whom the plots revolve, episode after episode, season after season, be they borderline, violent, or even openly racist.

FRANCE HAS BEEN SPARED THESE LIVELY DEBATES

All this representation is now being questioned, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and of civilians capturing instances of serious police misconduct directly on camera. Many shows are being accused of normalizing this behavior, from the 90s’ NYPD Blue – led by alcoholic, racist sergeant Andy Sipowicz – to Law & Order: SVU and its brutal detective Elliot Stabler. Even Brooklyn Nine-Nine, a comedy, hasn’t escaped critical ire – with all its portrayals of law enforcement officers in a likeable light, it has been accused of “copaganda.” Not to mention all the shows on American cable networks, which are free from the censorship that terrestrial stations are subject to, and accustomed to resorting to extreme measures – detective Vic Mackey of The Shield and marshal Raylan Givens of Justified being some of the more illustrious representatives of this trend over the past twenty years.

police dramas have always drawn their strength from the grey area where the limits of legality become distorted.

But another interpretative framework is possible, provided we remember one obvious fact: that morality and fiction are two distinct notions. Whether they are given a literary twist by Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammet, or more recently, James Ellroy, or whether they find in the film noir genre a stage for their impulses, police dramas have always drawn their strength from the grey area where the limits of legality become distorted. It is in light of this long tradition that one must read our fascination with marginal, or even deviant, serial detectives. Who would be interested in the trials and tribulations of Dexter were he not a serial killing righter of wrongs in the guise of a policeman?

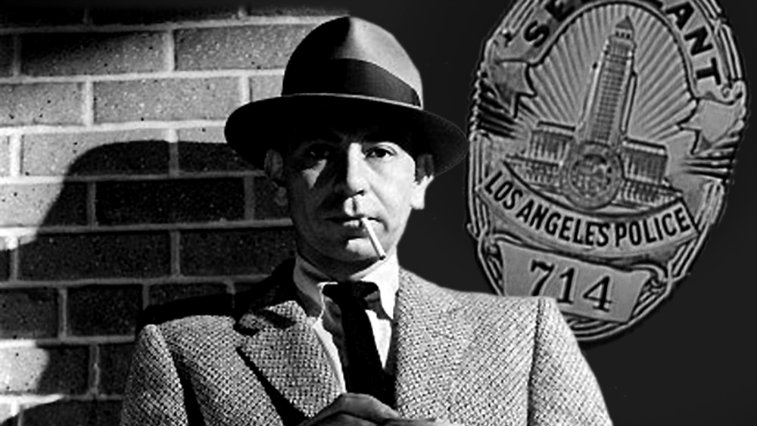

The origin of the discomfort lies elsewhere, but we would be wrong to just wave it off – the ties between serial fiction and the institution of the police in the United States are real, powerful, and historic. One example is the pioneering Dragnet, back in the 1950s, which marked the genre in a lasting manner. In order to gain access to certain filming locations in Los Angeles, as well as law enforcement equipment, Jack Webb, the creator of and lead actor in the series, granted local police vetoing rights on his scripts. If there is such a sustained relationship between the entertainment industry and law enforcement in Hollywood, it is because of this original pact, which would go on to become a sacred union. And while allowing screenwriters, filmmakers, and producers to regularly boast about the “realism” of their shows, it also quietly legitimizes the way the institution of the police works as a whole – including by justifying its excesses on screen.

It might seem surprising that France hasn’t been privy to these lively debates about the responsibility of televised fiction – after all, it too is beset with tensions between civilians and the police, and also counts, among its audiovisual output, a high percentage of police dramas. How to explain that our Alex Hugos, Captain Magellans, Léo Mattéïs, and other nationally recognized detectives have not also been the object of passionate discussions about the links between law enforcement and its representation in TV shows? Might we unconsciously have a more distanced reading of these shows, viewing them purely as entertainment? Or is this, in a more general way, about a different cultural and societal relationship to the law and to those who are tasked with implementing it?

ONE TOPIC, MANY POINTS OF VIEW

Those are doubtless factors of some importance, but there is another salient aspect to our police fiction: the focus on atypical characters. They are defined, from the start, by what makes them stand out within their own work environment. Whether that is a disability, their habits and obsessions, or their assertive eccentricity, our serial detectives are entirely different animals to their counterparts across the pond. Candice Renoir trying to strike the balance between her life as a mother and her job as a police chief; Caïn having to work from his wheelchair; Cherif projecting his TV-fanboy references onto his daily life; César Wagner struggling as a hypochondriac – these distinguishing features allow these people to become purely fictional characters. And incidentally, the shows they star in aim neither to examine the institution they portray, nor the society within which they exist.

How, then, do you revive a genre that is as old as TV itself and whose tropes are more than a little tired?

The popular Corinne Masiero as Captain Marleau and Eric Cantona in Le Voyageur (“The Traveler”) – both of whom are wholly in keeping with the tradition of the “loudmouth,” where the line between actors and their fictional alter-egos gets murky – embody, in this way, a certain essence of the French take on the genre: solitary, quirky characters carrying out investigations out on the margins, at arm’s length from their superiors – all of which is a far cry from American debates about the realism and violence of police shows.

How, then, do you revive a genre that is as old as TV itself and whose tropes are more than a little tired? By making room for other points of view: those of the victims, of the media, of the powers that be – room, in short, for a plurality of voices that lets you contextualize crime, a feat The Wire has become the gold standard for ever since it was launched by David Simon back in the early 2000s. But this is, much like Engrenages (“Spiral”) in France, a show that is broadcast on a paying channel, and thus inherently aimed at a niche audience.

Innovations specific to shows that are directed at a wider audience can be found if you look at some of our European neighbors: in Scandinavia, whose “Nordic Noir” wave and its melancholic approach to social realism has been attracting imitators ever since its seminal The Killing and Bron; and in the United Kingdom, of course, which is spearheading police show innovation, and whose productions like Line of Duty are not afraid to stare corruption in law enforcement in the face through internal investigations.

Finally, we’ll mention two more recent examples – two miniseries that, while they may not follow the classical “procedural” formula, are no less rich in teachings about how to reconcile dramatic effectiveness with clever realism. The first of these is Unbelievable (Netflix), which showcases two policewomen whose findings fall on the deaf ears of their superiors, and who are forced to investigate a series of rapes on their own, in close contact with the victims. The second is Laëticia (France 2), which takes a deep dive into an unbearable social context in order to glean an understanding of the terrible disappearance of a young woman. Both are fictional programs inspired by tragic news items; both have the huge merit of taking detectives off their pedestals episode after episode and putting them on the same plane as their viewership.