By Marion Miclet | @Marion_en_VO

For the past several years, the overall quality of TV shows has continued to improve, but they just keep getting shorter. However, for viewers, creators and streamers, long-running dramas and sitcoms are just as crucial to the television industry as the limited series. So why do they keep disappearing?

I know what you did last summer… you watched Suits! The legal drama, which first aired on USA Network from 2011 to 2019, was never buzz-worthy (except when cast member Meghan Markle became the Duchess of Sussex) and yet, it remains the most streamed show of 2023 in the United States. It accomplished the surprising feat after Netflix acquired the rights and put it on its landing page. Out of curiosity, laziness or affinity for the blue sky era, subscribers pressed play. Suits reached the platform’s Top 10, therefore reinforcing its visibility. So what does this solid, but unexceptional, drama have to offer? 134 episodes running 42 minutes each over the course of 9 seasons. Suits is not just a show, it’s a television marathon..

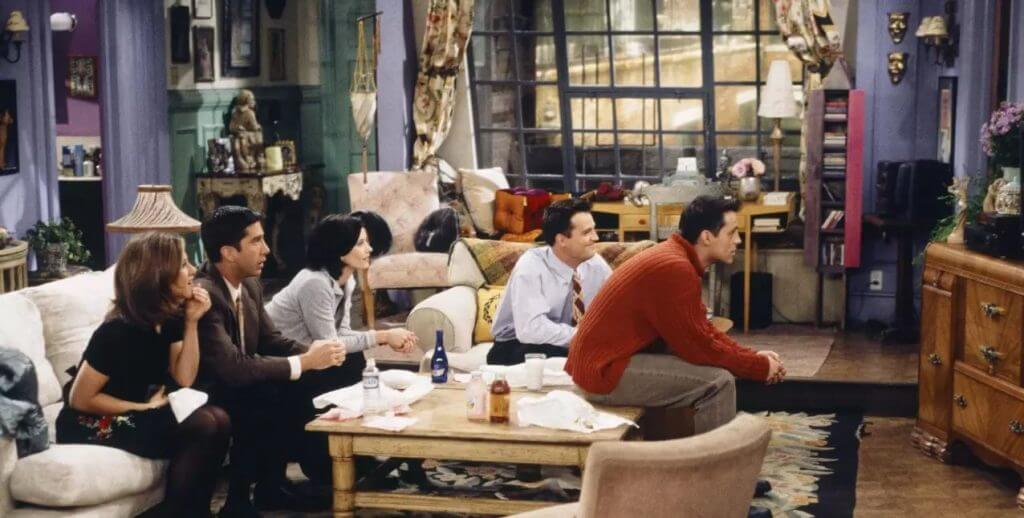

Just as with Supernatural, Gilmore Girls or The Big Bang Theory, Suits has the ability to keep you entertained for weeks – even if you are binge-watching. These meandering shows abound with twists and turns, recurring tertiary characters and inside jokes that reemerge two seasons later as if to ask “are you still here?” It is possible to start in the middle and skip several episodes (by essence, for procedurals) without getting lost (except for Lost, of course). During the COVID lockdowns, these extended series acted as our saving grace: we consumed them to feel less alone (Friends, Grey’s Anatomy), to be stimulated (The Sopranos, The Bureau), or to travel by proxy (Gomorrah, Elite).

Four years later, these marathon-series are still a huge part of our daily lives, especially if we enjoy them as ambient television, a phenomenon of the streaming era described by Kyle Chayka in a New Yorker article. However, they are becoming a rarity. Some are still alive (thanks to The Good Doctor), and kicking (the NCIS franchise recently launched a Sydney spin-off), but overall, double digits seasons shows on the air are an exception. And seasons are shrinking too: to quote Vulture’s Josef Adalian: “10 episodes is the new 13 (was the new 22).” How did we get here?

VINTAGE, STANDARDIZED, ENDEARING: THE LONG SHOWS OF YORE

You may have noticed that most of the popular long-running shows date back to the 1990-2000s. Nostalgia plays a part, but that doesn’t explain how Seinfeld and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air are being devoured by generation Z. The reward for those who start what seems like an endless watch is the development of parasocial relationships. The characters we fall in love with grow and evolve alongside us (this is particularly true of teen dramas that were produced on a weekly schedule). They help us forget, for a moment, about modern loneliness and the constant tug of social media. These TV sagas are endearing, but not addictive. And if you are enjoying them as a rewatch, they offer the perfect mix of intellectual relaxation and emotional engagement.

Secondly, the majority of shows that have endured the test of time hail from the United States. Compared to the United Kingdom, where Dr Who is an exceptionally vital veteran, and where seasons are traditionally much shorter (6 episodes or so), America is all about quantity. You’re not going to sit with the same appetite in front of The Office UK (2×7=14 episodes) and The Office US, which has more than 200 episodes (the longest season totals 28!). This cultural difference can be traced back to the glory of the network era thirty years ago, when marathon-series became a staple of American television and were exported worldwide.

Back then, storytelling followed a rigid calendar of 22 episodes per season, i.e. one episode a week from September to June. Pilot season was the most important event of the year in Hollywood, where the seeds of the long-running shows we are still consuming today would be planted. Once a project got greenlit, writers were expected to work at a relentless pace in order for each new episode to be finished on time, while also slowing down the overarching narrative arcs using cliffhangers, dead-end plot turns and bottle episodes (remember these?). The ultimate romantic trope to keep the viewers hooked was the will-they-won’t day, as seen in Friends (Ross and Rachel) and Parks & Rec (Leslie and Ben). More risky, the Lost creators kept adding new levels of intrigue to their already vacillating Jenga tower of a mystery, while ER jumped the shark by helicopter-amputating you-know-who in a late season.

Theoretically, these diluted television products are also aiming for excellence. They strike a balance between quantity and quality, which is the ideal compromise for fans, as well as the cast and crew. Indeed, network series are synonymous with stable (albeit exhausting) working conditions and the golden ticket : renewed and renegotiated contracts. For the talents, they provide a great opportunity to make mistakes and refine their craft, while launching their career and building a community of peers. As Matthew Perry confessed in his memoir, he had good and bad days on the set of Friends, but his co-stars always supported him. And let’s not forget the income that keeps coming from residuals after the series wraps, thanks to reruns. The Modern Family actors, who taped a whopping 250 episodes of the sitcom, could have probably retired after the final.

THE SHIFT TOWARDS AUTEUR SERIES AND THE EXPLOSION OF STREAMING

Aside from economies of scale, being able to last over the course of many seasons was a winning strategy for the networks at the time. First, it reassured advertisers. Second, reaching 100 episodes was the key that unlocked syndication, meaning that the rights to broadcast the show could be sold to local stations across the country. That’s when a long-standing series became profitable. However, that system wasn’t really applicable to the cable channels that started to dominate the TV landscape in the early 2000s (HBO, AMC, Showtime), since their business model was subscription-based. They functioned primarily by giving carte blanche to an inventive showrunner (sometimes for several years) without strict expectations of return on investment. That’s how masterpieces like Mad Men and Breaking Bad took their time to conclude, with a final season split in two. Considering it is almost impossible to maintain such high standards year after year (see The Walking Dead or The Crown), prestige TV now yields shorter seasons (9-10 episodes on average).

In that regard, Netflix didn’t really know how to position their first original series back in 2015. Their initial forays into content creation (House of Cards, Orange Is The New Black) were as complex and intense as the anti-hero dramas popular at the time. But the streamer also let the shows run their course for as many seasons as possible, because in the tradition of network television, longevity is associated with strength and legitimacy. Even though these early Netflix marathon-series were not broadcast live, they left a mark on television history and went on to win several Emmy Awards. That being said, this type of production was not sustainable. So it’s no coincidence that Netflix and their competitors have shifted to the genre of the mini-series. Unless they call for an extravagant budget, like WandaVision or Masters of the Air, their costs are, by definition, limited and they are a magnet for movie stars wishing to dip their toes into the world of television. There is also no risk of alienating fans because of early-cancellation. Speaking of which…

In order to attract subscribers, streaming platforms have pivoted away from extended series, preferring instead the “strategy” of throwing spaghetti at the wall and seeing what sticks. Inaugural seasons are not necessarily released in their entirety to become the first chapter in a continuing saga, but rather they serve as a pilot: they have to be a hit just to get greenlit. This frantic search for the new it show is of course incompatible with the dedication required for the production of a marathon-series. Hence their decline? Well, maybe not. Let’s go back to Suits. According to Rolling Stone’s Alan Sepinwall “It’s the sort of series Netflix has largely resisted making for itself, but that its subscribers clearly crave.” Its belated success is a clear indication that streamers must continue to invest in durability, just as much as in novelty.

As explained by Will Gorfein, CEO of Peerlogix, high-quality TV shows with an extended run possess an undeniable binge factor that makes them a valuable commodity in the race to retain subscribers. That’s what the streaming wars are all about. So, now that we are entering a new, more mindful, phase of television production with the decline of Peak TV and the aftermath of the Hollywood strike of 2023, is it time to forget about the hare and give another chance to the tortoise?